Media

VIDEOS

Media

VIDEOS

AUDIO

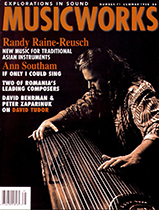

You'd think someone as busy as Randy Raine-Reusch would live in a more cluttered place. Except for the kitchen nook jammed with his computer, books and papers, the two-bedroom, East Vancouver house that he rents with a friend is sparsely clad, yet homey. We sit on legless, cushioned folding chairs on the carpet, in a dimly lit living room modestly adorned with Japanese wall hangings and a few plants. Where most Canadian homes entertain a couch, there stands Raine-Reusch's koto (a Japanese zither).

Today, over 600 traditional, world instruments that he has collected over the years fill a small, unfinished room in his basement, transforming it into a virtual living museum. On dozens of them, he creates improvisationally based compositions that merge traditional world musics with contemporary classical aesthetics.

Raine-Reusch lives for months at a time in Far East countries studying with "Master" musicians--from rice farmers to National Treasures--to improve his technique and deepen his musical understanding. Players from Korea, China, Vietnam and Japan join him in performances of traditional song and modern improvisation. Vancouver's Chinese community invited him to play his guzheng (a Chinese long zither) as a featured artist during their 1996 Chinese New Year celebrations. In March 1998, he had the rare honour to perform his ichigenkin (a one-string Japanese zither) on stage at the Canadian Consulate in Tokyo, with Japan's Iemoto of Seikyodo Ichigenkin (hereditary head of the traditional style of ichigenkin in Japan).

His world music group, ASZA, which was nominated in 1997 for a Juno award, recorded their first CD two years ago and performs regularly around the world. Currently, Raine-Reusch is at work on a piece for nigenkin (a rare, two-string Japanese zither) for an upcoming tribute CD, produced by Victoria-based composer, Bob Priest, of original compositions based on Jimi Hendrix's music. Raine-Reusch also works to record and preserve the indigenous music of Borneo.

How does this man find the time to pursue and accomplish so much?

"I've always been this way," he replies. "I am a survivor of a dysfunctional upbringing. The abuse fractured my psyche and quashed whole parts of my being, which is partly why I do so many things, and at once. Through all my endeavors, I'm expressing the many parts of myself and bringing them together into the one person that I am. I'm actually doing one thing; I'm attending to many branches of the same tree."

The seeds were planted in 1952 in Halifax, Nova Scotia where Raine-Reusch was born and lived until age five when the family moved to Vancouver. Growing up, there was no music in his lower- middle-class home, until his first accordion lessons, at age eight. However, because of extremely poor eyesight, he couldn't read the notes, so he randomly pressed the keys, instead, and discovered a world of tones, listening to them for hours. The "noise" annoyed his parents who quickly sold the instrument. But Raine-Reusch simply turned to a school piano and, later, the saxophone his school music teacher handed him.

With his poor eyesight and keen hearing, Raine-Reusch realized he saw and heard things no one else he knew did. He became attracted to the spiritual, and by age 15 realized, if anything, he was a Taoist. Meanwhile, his short-wave radio acquainted him with electronic music, and the library introduced him to blues, jazz and world musics.

"Finding music was like discovering a secret garden that I could escape to," says Raine-Reusch. "I could be happy and excel there, and nobody could take that away from me."

In his 20s, after a year at the Victoria Conservatory of Music, in Victoria, British Columbia, he took up the Appalachian dulcimer and went to the Creative Music Center in Woodstock, New York, in the late 70s. There he studied and improvised with free jazz musicians Karl Berger, Jack Dejohnette, Dave Holland and Fred Rzewski.

Over the next several years, he bought African lutes, a guzheng and other world instruments from junk stores, and taught himself how to play them by imitating what he heard on records. Ultimately, Raine-Reusch found it easier to learn and read Japanese and Chinese notation over Western music's "rabbit droppings," as he puts it, because there were no staff lines that moved when he looked at them, given his impaired eyesight. But it wasn't until his first trip to Asia, in 1984, that he began to seriously study Asian music.

A small Canada Council grant paid his way to Thailand where Nukan Srichrangthin, a poor rice farmer, recognized as the best khaen (a free-reed mouth organ) player in the world, spent seven hours a day teaching Raine-Reusch. "I practiced another four and I still couldn't grasp the rhythms or the feel of the music at all," he says. "Then, one day with my teacher, I felt my brain turn sideways and I instantly understood, deep within myself, how the music worked, but I couldn't intellectually explain it. My whole way of being changed then, and that's when my lessons really started."

Thus began a series of trips to countries in the Far East and South Pacific, to study with a wide variety of musicians and masters. "I felt an affinity with traditional Asian music. I liked its attention to introspective and philosophical aspects. >From studying it, I found nourishment, but I also found I had a lot more to learn," says Raine-Reusch.

Studying the instruments reinforced everything he had taught himself about sound, music and listening, when he'd pluck one note for hours, giving his all to a single sound, from attack to decay.

"I realized the context of the sound is more important, in some senses, than the sound itself," says Raine-Reusch. "The sound is a medium; it's not the real content. Where and what am I producing this sound from? Why? What is that sound's relationship to my environment? These are all questions that musicians have asked for thousands of years, and I felt I needed to be mindful of them if I was going to make a sound."

Creating his own music always remains Raine-Reusch's intent in his study on traditional instruments. "He won't be the top traditional player because he wasn't brought up in the culture," says Qiu Xia He, Vancouver lute player and ASZA member. "But if you ask him to play for other Chinese people, they'll say 'Wow,' because of how he approaches the instruments. He uses traditional techniques but applies them in a contemporary way." Raine-Reusch specializes on about eight instruments, including the khaen, guzheng, ichigenkin and the Korean kayageum (a 12-string long zither). He comfortably plays over a hundred others, and can demonstrate various techniques on the remainder of his collection. Playing these requires that he step outside of his world and learn a entirely new musical culture. "In the Western tradition, music is often considered to be found in the 12 notes of the scale. But in Asia, it's found between these notes," says Raine-Reusch. "To play Asian music, it has taken me years to learn a whole new way of listening, thinking and even moving."

Jungae Lee, a well-respected kayageum player in Vancouver, appreciates that Raine-Reusch grasps some of the most important elements of Asian music. "Randy understands the feeling of Korean music," she says. "For example, there is happiness but not this Western feeling, not delightful. It includes sorrow as well, but it can be expressed as happiness. He understands this spiritual feeling and sometimes this is communicated in his music."

"You may get better musicians within a specific country, as national treasures," says Stuart Dempster, Seattle-based composer and improviser on trombone and didjeridu, who has played with Raine-Reusch. "But I haven't seen anyone who has taken this kind of world view to music."

For both his compositions and improvisations, Raine-Reusch uses traditional techniques, creating a new piece in the classical style of a culture's instrument. He then begins a long process of ongoing revisions of the piece, which becomes more contemporary as it progresses. Along the way, he incorporates new tunings; tonalities; and techniques and concepts from related instruments. Jazz, experimental, world and new musics also find their way into his work, as well as other instruments, live sound sources (dripping water, falling leaves, snapping twigs) and computer-generated sounds.

Says Paul Plimley, Vancouver experimental jazz pianist who has improvised with Raine-Reusch, "Randy is performing a noble task in that he's utilizing Asian instruments, philosophies and spiritual mind sets that apply to centuries of playing music, but he's not replicating those classical traditions. Rather, he's assimilating what's useful, natural and stimulating for him, so he can adjust and incorporate aspects of those traditional languages into his own, unique vocabulary and approach to making music. He ends up transforming those Asian influences to come up with a personalized approach to improvising in a way that speaks more about who Randy Raine-Reusch is than the traditions of Asiatic music-making."

Some people, however, may see Raine-Reusch as a "cultural bandit," one that skims off aspects of traditional music that are more potentially palatable to Western tastes, and pours them into his own global goulash that has little or nothing to do with the original culture and its cumulative spiritual meanings. Fellow improviser, Kingston, New York's Pauline Oliveros, accordion player and founder of Deep Listening, says, "It's a delicate position being a white male, which is often seen as the exploiter. I think of Randy as a bridge between Asian and Western practice . . . He makes every effort to understand the cultural aspects of his instruments."

Robert Dick, internationally known American avant-garde flute player, and Barry Guy, British bass player and composer, improvised with Raine-Reusch at the 1997 Vancouver Jazz Festival and recorded a soon-to-be-released CD, produced by Russ Summers. Says Dick, "When I see trees growing on the roofs of burned-out houses in Harlem, or a vine's root hairs holding the earth through a tiny crack in a concrete wall, I think of musicians like us. . . Randy is an original, and is putting his life together out of a jigsaw of elements . . . He presents a unique voice that is like some kind of musical airline hub with undelayed flights to everywhere."

Improvisation forms the basis of Raine-Reusch's original compositions. His scores combine Eastern-influenced graphics, the occasional Western notation, calligraphy and poetry. Each is accompanied by several lines of written instruction for the performer. Raine-Reusch's piece titled, "The Warmth of Stone" suggests:

Although written for Chinese guzheng, a twenty-one or twenty-three string long zither, other instruments may be substituted.

A deep awareness of stone is suggested. The performer may wish to sit listening with a stone for a long time.

This score can be performed by playing only the pitches indicated, or by playing all pitches except the pitches indicated, but always includes playing stone.

This score does not need to be performed to be performed; it is performed by being regarded.

The scores direct the player's state of mind, listening or being, rather than tell him or her to play a particular note. They also live as independent works of art that visually express the complexity of Raine-Reusch's feelings that he wants performed--no different than anyone else's scores, except for the language he uses.

"Some people balk at my scores because they think they're flights of fancy or New Age-y, but they just don't understand," he says, reflecting the isolation from others that he often feels.

While his scores make little or no connection with some people, for others, they can reveal themselves right away or slowly over time. Some people see the scores as an interpretation they instantly recognize, and believe in--perhaps even have longed for--not something they have to struggle to figure out. "There are few people I've met who share my perceptions, and it's lonely because of that," says Raine-Reusch. In the search for like-minded souls, his scores serve as beacons, lighting the way for others to find him.

John Cage, whom Raine-Reusch met just two days before his death in 1994, validated his expression to write any way he chose, "and that it was not only OK, but it was the only way to do it," he continues. "Both John and Pauline were the first people who recognized some of the deeper aspects of my music. I finally felt accepted. If not for them, I don't think I'd write and play the way I do."

Cage; Oliveros; Yuji Takahashi, pianist; Kazue Sawai, koto virtuoso; Toru Takemitsu, composer; and Malcolm Goldstein, violin improviser, are among those with whom Raine-Reusch feels an affinity. Their friendship and support have provided fellowship, and helped him strengthen his sense of self, musically and otherwise.

His growth as an artist has given him a deeper appreciation of the need to preserve the original sources of music he relies on. Recently, he travelled to Borneo, where he recorded and produced two CDs of indigenous music, in an effort to maintain and promote the traditional music there.

In 1997, while in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, he found that the traditional music was rapidly being replaced by influences of modern culture. It took two more trips and several months to procure local government permission to record, with sponsorship from the Canadian Society of Asian Arts and Malaysia Airlines. Significant financial support was obtained from Borneo's former Deputy Secretary of State, Datuk Taha Ariffin, through his newly formed company, Tamar Holdings, as well as the Sarawak Tourist Board and Majlis Adat Istiadat (a legal society for the indigenous people). The recording, titled "Sawaku: The Music of Sarawak" was released on Holland's PAN Records in March 1998.

In Borneo, Raine-Reusch also assisted the Sarawak Tourist Board in organizing a group of traditional musicians and dancers --who had never before left the jungle--to perform in Marseilles, France in January 1998. They accepted the invitation of Ben Mandelson, the director of WOMEX [World of Music Exposition] to participate in this international world music conference. Currently, a booking agent is organizing a European tour. It doesn't stop there. Raine-Reusch is also stimulating the Borneo people to make more, traditional instruments, for both social and commercial interest. These include the krommoi (a percussion instrument, made from two snail shells, that imitates the sound of a frog), sape (a boat lute carved from a tebulon tree) and keluri (a bamboo mouth organ). With the Sarawak Tourist Board, he is working to mount the Rainforest World Music Festival. The annual, weekend event will feature dozens of local and international artists, and debuts August 1998 in Sarawak. A film of traditional Borneo dance and music is also in the works. "I want to see the music survive in Borneo," says Raine- Reusch. "Most of it is vanishing along with its associated, traditional rituals. I'm helping to provide opportunities for the indigenous people to play their music and share it with the world."

He tells me the story of Tegit, a subsistence farmer and Borneo's best sape player, who had barely stepped out of his Sarawak long house before he boarded that plane for France. "It was the shock of his life. For the first time, he rode moving sidewalks and elevators, flew above the ocean and ate croissants," says Raine-Reusch. "There we were standing at the edge of the Mediterranean one morning in Marseilles when he said to me, very quietly, 'I don't want to die. I want to see all this, first.' It was just beginning for him."

And for Raine-Reusch, as well. "There's a kid in me that has yet to be born, and I want to give him life," he says. For him that means going back to the Borneo jungle, around the world and, as always, deep inside himself to the place where his expression of music continues to grow. It means spending many more years of study with master performers in their own countries, writing scores that some people may scoff at, and playing music that will move others to tears. It means, at times, aspiring to do absolutely nothing.

"As a child, I couldn't just wake up in the morning and feel the sunlight on my skin and go, 'Ah,'" he tells me. "It's hard for me not to clutter my mind with ten million things and read thousands of meanings into something, which is typical of the kind of compulsive behaviour that can plague people who have been abused as children. But I think I'm getting there."

So it doesn't really surprise me when I ask Raine-Reusch one final question: If you had just one minute left of your life to say something with music, what would that be?

"I'd make no sound whatsoever," he says without pausing to think. "Either that or I might give you a rose petal."

The scores direct the player's state of mind, listening or being, rather than tell him or her to play a particular note. They also live as independent works of art that visually express the complexity of Raine-Reusch's feelings that he wants performed--no different than anyone else's scores, except for the language he uses.

"Some people balk at my scores because they think they're flights of fancy or New Age-y, but they just don't understand," he says, reflecting the isolation from others that he often feels.

While his scores make little or no connection with some people, for others, they can reveal themselves right away or slowly over time. Some people see the scores as an interpretation they instantly recognize, and believe in--perhaps even have longed for--not something they have to struggle to figure out. "There are few people I've met who share my perceptions, and it's lonely because of that," says Raine-Reusch. In the search for like-minded souls, his scores serve as beacons, lighting the way for others to find him.

John Cage, whom Raine-Reusch met just two days before his death in 1994, validated his expression to write any way he chose, "and that it was not only OK, but it was the only way to do it," he continues. "Both John and Pauline were the first people who recognized some of the deeper aspects of my music. I finally felt accepted. If not for them, I don't think I'd write and play the way I do."

Cage; Oliveros; Yuji Takahashi, pianist; Kazue Sawai, koto virtuoso; Toru Takemitsu, composer; and Malcolm Goldstein, violin improviser, are among those with whom Raine-Reusch feels an affinity. Their friendship and support have provided fellowship, and helped him strengthen his sense of self, musically and otherwise.

His growth as an artist has given him a deeper appreciation of the need to preserve the original sources of music he relies on. Recently, he travelled to Borneo, where he recorded and produced two CDs of indigenous music, in an effort to maintain and promote the traditional music there.

In 1997, while in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, he found that the traditional music was rapidly being replaced by influences of modern culture. It took two more trips and several months to procure local government permission to record, with sponsorship from the Canadian Society of Asian Arts and Malaysia Airlines. Significant financial support was obtained from Borneo's former Deputy Secretary of State, Datuk Taha Ariffin, through his newly formed company, Tamar Holdings, as well as the Sarawak Tourist Board and Majlis Adat Istiadat (a legal society for the indigenous people). The recording, titled "Sawaku: The Music of Sarawak" was released on Holland's PAN Records in March 1998.

In Borneo, Raine-Reusch also assisted the Sarawak Tourist Board in organizing a group of traditional musicians and dancers --who had never before left the jungle--to perform in Marseilles, France in January 1998. They accepted the invitation of Ben Mandelson, the director of WOMEX [World of Music Exposition] to participate in this international world music conference. Currently, a booking agent is organizing a European tour. It doesn't stop there. Raine-Reusch is also stimulating the Borneo people to make more, traditional instruments, for both social and commercial interest. These include the krommoi (a percussion instrument, made from two snail shells, that imitates the sound of a frog), sape (a boat lute carved from a tebulon tree) and keluri (a bamboo mouth organ). With the Sarawak Tourist Board, he is working to mount the Rainforest World Music Festival. The annual, weekend event will feature dozens of local and international artists, and debuts August 1998 in Sarawak. A film of traditional Borneo dance and music is also in the works. "I want to see the music survive in Borneo," says Raine- Reusch. "Most of it is vanishing along with its associated, traditional rituals. I'm helping to provide opportunities for the indigenous people to play their music and share it with the world."

He tells me the story of Tegit, a subsistence farmer and Borneo's best sape player, who had barely stepped out of his Sarawak long house before he boarded that plane for France. "It was the shock of his life. For the first time, he rode moving sidewalks and elevators, flew above the ocean and ate croissants," says Raine-Reusch. "There we were standing at the edge of the Mediterranean one morning in Marseilles when he said to me, very quietly, 'I don't want to die. I want to see all this, first.' It was just beginning for him."

And for Raine-Reusch, as well. "There's a kid in me that has yet to be born, and I want to give him life," he says. For him that means going back to the Borneo jungle, around the world and, as always, deep inside himself to the place where his expression of music continues to grow. It means spending many more years of study with master performers in their own countries, writing scores that some people may scoff at, and playing music that will move others to tears. It means, at times, aspiring to do absolutely nothing.

"As a child, I couldn't just wake up in the morning and feel the sunlight on my skin and go, 'Ah,'" he tells me. "It's hard for me not to clutter my mind with ten million things and read thousands of meanings into something, which is typical of the kind of compulsive behaviour that can plague people who have been abused as children. But I think I'm getting there."

So it doesn't really surprise me when I ask Raine-Reusch one final question: If you had just one minute left of your life to say something with music, what would that be?

"I'd make no sound whatsoever," he says without pausing to think. "Either that or I might give you a rose petal."

Randy Raine-Reusch is just back from Southeast Asia and he's already looking for a museum of ethnomusicology. Not one to visit, but one to house the collection of more than a thousand instruments he has accumulated in the course of his many trips to the continent. It's not just that he doesn't have adequate room for them all, while he was in Borneo last month his garage burned down, and he's worried. "Many of these instruments are rare," he confides in the course of an interview in his East Vancouver home, on the day of his return. "And some are simply not replaceable."

The main purpose of the latest journey wasn't, however, to collect more instruments. Raine-Reusch has been hired by the Dutch label Pan to make field recordings of traditional musicians in the Malaysian province of Sarawak (on the northwest coast of Borneo) and subsequently to produce a CD of their music. There are eight major cultural groups in Sarawak, with 28 distinct subgroups. "Some of them are extremely remote," says Raine- Reusch. "Some only play at particular times of year, and some only perform in sacred ceremonies that are not allowed to be recorded. But I've got a fair sampling as a first stab, and hopefully I can continue in years to come."

Along with the Melanau and Chinese populations of the coast, and the nearby Bidayuh, Raine-Reusch recorded the Iban and Orang Ulu peoples of Sarawak's interior. The Orang Ulu, which means the "upriver folk", are the most difficult to reach. They live in the highlands, where you have to do the toughest jungle travelling - that means two-day boat rides and up to 16 hours in a Land Cruiser on logging roads. Once it rains there in the rainy season, which is just finishing, the roads turn to a mud so slippery you can't stand up on it. So driving is very hazardous, but it's all part of the excitement. I recorded music on the sape - a beautiful Instrument akin to a lute - some on both bamboo and metal jaw harps, the nose flute, the tube zither, the gong, the drum - as well as vocal music.

Raine-Reusch also recorded material played on the keluri - a type of mouth organ made out of a gourd, with six bamboo pipes emerging from its top. It was this instrument, a distant ancestor of the harmonica, that first led him to Sarawak in 1989. "The keluri was traditionally used by the Orang Ulu in line dances that were part of different ceremonies, such as dances by women in honour of returning headhunter parties. As the culture has changed - with the arrival of Christianity and Islam, among other things - the dances aren't performed any more, and the keluri has almost gone. I've only met two men, the youngest of whom is almost 60, that can play well, have a full repertoire, and remember the dances."

"It's funny that though keluris have almost vanished upriver, in Kuching [capital of Sarawak] there's something of a revival - for which I'm partly responsible," continues Raine-Reusch. "I bought a whole bunch in town, and that spurred a number of other people to go and buy them. They didn't know how to play, so I taught them what I'd learned from listening to tapes in a museum and meeting the few remaining musicians. I've just ordered 50 to be made and I said I might want another couple of hundred in years to come. My whole idea is to stimulate the manufacture of these instruments again, and to train some young guys to do it, so the keluri can survive. The Orang Ulu don't even grow the gourds any more. I've been asking people from a region where they're still found to give me seeds. It will all take a few years, but hopefully I'll be successful."

Raine-Reusch has brought back five keluris, along with assorted flutes, jaw harps, a couple of traditional gambus (related to the familiar oud of the Arabic world), and an Iban drum, "The Iban are hard-core drummers, and were also the fiercest of the headhunters," Raine-Reusch explains. "It's really something to see these guys. Some of them are tattooed from head to toe. The traditional designs are stunning, though nowadays eagles and motorbikes are starting to appear. But it's hard to get to hear their music, because there have to be ceremonies before they'll play, so I was fortunate to be able to make some recordings."

"One of the things the Iban men do is to sit in a circle and drum, using interlocking rhythms in a kind of drinking competition," he goes on. "While they drum, they pass a glass filled with a very potent rice wine with their right hands. The rhythms are complex, and must be maintained. If anyone falters, he has to drain the whole glass in one gulp. Then they continue around again. Usually, it's the same guy who makes a mistake, and he gets drunker and drunker and drunker. It's quite hilarious but requires an amazing amount of skill. I've got that on both tape and film. The rice wine is famous for making your joints ache next day. Not only does your head hurt, but your whole body is screaming in pain!"

In addition to collecting and recording unusual ethnic instruments, Raine-Reusch also plays many of them himself - mainly with Asza, the Vancouver-based world-music quartet he helped to found five years ago. He's particularly pleased to have brought back several examples of a bizarre percussion instrument known as a kromoi - enough for every member of Asza to play. The kromoi consists of two large snail shells stuck on either prong of a bamboo "fork". The two shells touch, and when a small stick is passed rapidly between them they strike one another repeatedly. "Up close you can hear the hard ring of the shell," says Raine-Reusch. "But at a small distance, and with a number of them played together, they sound exactly like rain-forest frogs. In fact, they re used to call frogs. ItÕs really quite exciting!"

It's a busy time for the musicians of Asza, who are involved in a range of projects, as individuals and as members of other bands. Raine-Reusch is off to Borneo again in the spring to continue his recordings, but before that he travels to Japan to play the ichigenkin, a traditional single-string instrument, in a concert with the Iemoto (hereditary head) of the main ichigenkin school in Tokyo. "I studied there some years ago, and they were shocked that I would improvise music. So then I started to teach the Iemoto, which is unheard of. WeÕll be doing some improvisation together, and one of my pieces as well. She wants to tour with me internationally. It's a high honour and I'm pretty excited - and just a bit nervous," adds Raine-Reusch with a laugh!

KUCHING, Malaysia - Music may not be the first thing that comes to mind at the mention of Malaysia, but that may change if Canadian musician Randy Raine-Reusch succeeds in his mission.

Raine-Reusch has been commissioned by Sarawak's tourist authorities to help this Malaysian state on the island of Borneo to tune up to the world beat. He says Malaysia is sitting on a goldmine of traditional music that is bound to entrance listeners from elsewhere. The Canadian's enthusiasm for Sarawakian music precedes his hiring by the state. In fact, it was partly because of his excitement over his musical ''find'' a few years ago that officials here finally decided it was time to realize their dream of putting Sarawak on the world music map.

Sarawak has some 26 indigenous ethnic groups, each with its own musical culture. But because these peoples have traditionally lived in communal longhouses in the forests, cut off from the towns and cities, urban Malaysians are themselves unfamiliar with Sarawakian music.

These days though, Raine-Reusch and Sarawak officials are thinking beyond Malaysia's borders. Indeed, for the last two years, they have been holding a Rainforest World Music Festival that highlights not only Sarawakian sounds but also other indigenous music from all over the world. Organizers and participants say the festival exposes local musicians to world music while also introducing outsiders to the musical instruments and melodies of Sarawak.

The second festival, held last month, brought together musicians from Sarawak, East Malaysia, Cuba, Madagascar, Peru, Scotland, Canada and China. ''We want to bring down our musicians from the longhouses and the kampongs [villages] in the interior and expose them to the international musicians who are here,'' explains Mohd Tuah Jais, chairman of the festival organizing committee. ''This is where creativity comes in, to see whether you can blend your kind of music with that of the other groups.'' Sarawakian music would be a welcome addition to an industry that is gradually going truly global. Until the so-called ''world music'' took off in the 1990s, most new musical forms and styles originated in the West, especially in the United States, even though their roots may have been in Africa or South America.

But now indigenous music and cultural values of Asia, Africa, South America and many other parts of the non-Western world are been exported to other regions without having to adapt Western musical idioms to be successful. Western musicians are now the ones adapting other musical forms and instruments, such as the Indonesian gamelan, the Japanese shakuhachi and the Indian tabla, into their own music.

Both Raine-Beusch and Mohd are betting that the Sarawakian traditional guitar, the sape, will be the next non-Western musical instrument to take the world music scene by storm. Observes Raine-Reusch: ''There's a style of music from West Africa called Kora which has been selling well. Sape music has that same appeal.'' Sape is a ''boat-lute'' played by the Orang Ulu or the upper river people of central Borneo. Often used to accompany songs and dances, the Sape traditionally had only two strings, but now three, four and even five-string instruments are common. Most musicians now play it amplified with an electric guitar pickup.

''Some foreign musicians now identify the music of Malaysia from the sound of the sape,'' remarks Matthew Ngau Jau, one of Sarawak's leading exponents of the instrument who has recently given concerts in Germany and France. He says the sape was traditionally played in longhouse ceremonies, but had begun losing appeal among the younger Sarawakians who preferred to play the guitar. Ngau Jau says the recognition sape is getting overseas now may change all that. Community leaders, however, have criticized previous attempts to modernize traditional Sarawakian music, saying that such attempts corrupt local musical cultures. But Mohd points out that blending traditional music with Western instruments may just be the ticket to getting outsiders interested in what Sarawak has to offer musically.

''Many traditional ceremonies and rituals are disappearing,'' Raine-Reusch notes. ''That's why we're not seeing young musicians playing this music. They are playing rock-and-roll. Because the rituals are dying, the only way to keep the music alive is to change the context of the music. So we switch to performing music. It does change the music, it's true. But it helps to allow the music to survive and may even allow it to grow and change.''

A Slice of the Du Maurier Jazz Festival, Vancouver, BC: 24-26 June, 2001

The Vancouver Du Maurier Jazz Festival is one of many that occur annually in Canada, one which is earning a competitive reputation for assembling the most colorful threads of the jazz tapestry in a most timely fashion. This 16th year featured more than 1500 jazz musicians from around the world, performing at over forty different venues. Du Maurier's organizers have their ears close to the rails of the jazz progression, thus booking in advance such headliners as Dave Douglas, John Scofield, Louis Hayes, Curtis Fuller, Joshua Redman, Roy Hargrove, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Tim Berne, and Ellery Eskelin's acclaimed trio with accordionist Andrea Parkins and drummer Jim Black. For all of these promising acts, the most anticipated event of the festival took place within the opening weekend--the Barry Guy New Orchestra, an international concoction of some of the most prolific instrumentalists in contemporary jazz. …For two days prior to the New Orchestra's single performance on Sunday night, the musicians could be heard in a variety of settings spread across four separate venues, each of the exhibitions a marathon of free improvisation unto itself. The performances were both primer and filler for hungry audiences.

On Friday, opening night of the festival, Barry Guy and Mats Gustafsson joined Vancouver composer/instrumentalist Randy Raine-Reusch for a set of meditative free improvisation. Raine-Reusch, a master of eclectic East Asian wind and string instruments, was perfectly suited for the foundation laid by Guy and Gustafsson, which was a blend of their own telepathic skills and the uniqueness of the setting itself. The stage was the limestone floors of Dr. Sun Yat-Sen's Chinese Classical Garden, in the Chinatown section of Vancouver.

The garden is said to be "a microcosm of nature and man's place within it." Honored for the early-20th century Chinese leader of the same name, it is a stunning call back to the architecture of the Ming Dynasty, adorned with mahogany wood, ornate tile patterns, bonsai trees, bamboo, and a contemplation pool brewing with Koi fish.

It was a natural atmosphere for the trio, who seemed to play not just for their audience, but also as an extension of the serene elements of their surroundings, both organic and immaterial. The trio settled into the first piece with Raine-Reusch blowing a sumpoton--a Sabahan mouth organ with several reed-fitted pipes affixed to a gourd wind chamber. Guy joined on bass with Gustafsson close behind on tenor saxophone, and soon the trio was engaged in a thirty minute improvisation that was as incomprehensible as it was awe inspiring. The unsuspecting audience was taken for a colorful ride that called to Eastern mysticism and the permutations of European free improv alike. As remarkable as the trio played, nothing was more endearing than the way in which music fused with environs. At one point during the set, with Gustafsson taking a soft solo on fluteophone--Gustafsson's creation, a flute outfitted with themouthpiece of a saxophone--a small group of gulls soared overhead, inspiring a brief burst of call and response between the birds and the reedman. Other pieces featured Raine-Reusch on two fretless Chinese zithers, using fingers, slides, brushes and mallets to extract a mélange of tones and inflections. During the second improvisation, following an excursion colored by straight ethereal tones from each instrument, Guy constructed a weighty solo, moving violently up and down the strings. With intense and concentrated energy, he maintained communication with his stage mates; upon hearing percussive tones from the Chinese zither, Guy began mimicking with mallets on the strings of the double bass. Gustafsson occasionally came alive on baritone saxophone and Guy never failed to push the group into new territory with thoughtful submissions and an against-the-grain idealism that was both commanding and stimulating.

At show's end the audience stirred and reflected. Some attempted to deconstruct the sounds that were experienced, others engaged in the judgmental diarrhetics that so often plague the free jazz crowd--"Wow, that was…well, I don't know. Fantastic." "A perfect match, Randy was amaaaazing." ...

ALAN JONES, One Final Note - Issue#7-8, summer/fall 2001

Han and Raine-Reusch have redefined the zheng, and challenged the world of traditional Chinese music in general. Together they have invented new tunings, developed new fingering techniques, expanded old structures and created radical new forms of expression on this ancient instrument. China Daily, Beijing

ERAS, Randy Raine-Reusch & Michael Red, 2024/25

Veteran Vancouver-based multi-instrumentalist, composer, and world music pioneer Randy Raine-Reusch and electronic musician, composer, and DJ Michael Red join forces in six deep sonic meditations on ERAS.

The project has a fascinating backstory: back to 2014 when Red met Raine-Reusch in the latter’s home- world instrument-museum. Raine-Reusch is not only a noted instrument collector but has also spent his career studying and playing them. He specializes in performing and composing experimental music for instruments from around the world, particularly those from Asia.

During their 2014 recording session, Raine-Reusch chose various acoustic instruments from his vast collection including Asian flutes and various string zithers, African harps, and gongs. Adopting an intuitive interactive process, the duo recorded their finely-grained and honed improvisations, Red electronically processing them. The album was completed over the course of several days, but rather than immediately releasing it, they chose to leave it “to mature and distill.” The duo decided to finalize Eras this year, being “careful to preserve the direct and intuitive process that permeates the recording.”

Evocative track titles such as Five Names of Peace, Shifting Silence, Inner World and Winter Water capture the meditative, slowly flowing focus of the music. Between Is Six, the opening track, sets the tone with Raine-Reusch’s sensitive breath-centred sounds made on a low flute, sensitively modulated over the stereo sound stage by Red. And the last album sound is the most exquisitely languid fadeout I’ve heard all year.

How to sum up the music on Eras? Rather than New Age, descriptors such as shadow worlds, sonic incantations and dreamtime may make more sense.

WholeNote Magazine, by Andrew Timar, February 2024.

Bamboo Silk & Stone, Randy Raine-Reusch with Jon Gibson, Stuart Dempster, Jin Hi Kim, William O. Smith, Barry Truax, 2004

Distant Wind, Randy Raine-Reusch & Mei Han, 2001

Gudira, Randy Raine-Reusch, Barry Guy, Robert Dick, 1988

Nullam id dolor id nibh ultricies vehicula ut id elit. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus.

Driftworks / In the Shadow of the Phoenix, Randy Raine-Reusch & Pauline Oliveros, 1987

The four tracks feature Oliveros playing her signature accordion (tuned in just intonation, the Pythagorean tuning also favored by Robert Rich), joined by reed player Randy Raine-Reusch on three Asian instruments: the khaen, the sho and the dan bau. On each track, the two musicians take off in two separate directions, alternating between drawing abstract melodic lines and extended drones that only occasionally meet each other briefly before moving on to new explorations. This album clearly challenges the listener to engage in "deep listening," and unlike much other textural music, does not leave open the option of being used as "background" sound. Susqu.edu